Should Science Leave Universities Behind?

Scientists may have more freedom at private institutions than academia.

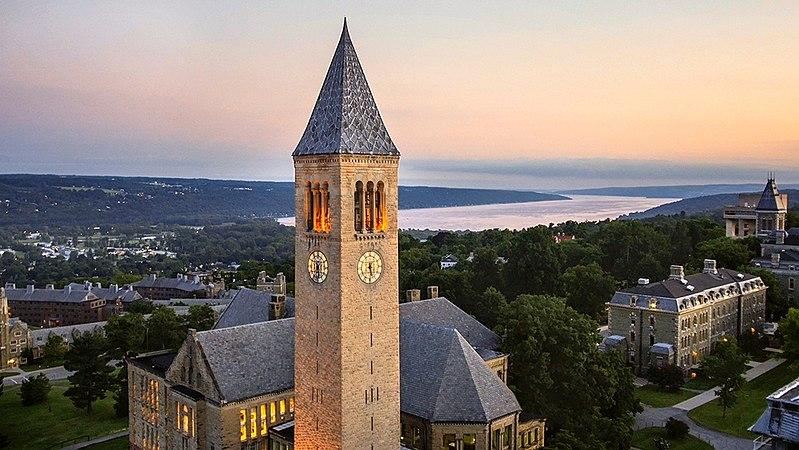

Cornell University. Credit: Wikimedia.

A dozen years ago, National Association of Scholars President Peter Wood posed the provocative question: Could science leave the university?

Wood framed his question in practical terms. There has always been a bargain of sorts between universities and their science faculties. Universities provide the means for scientists to do science—laboratories, students, bookkeepers, etc. Scientists hustle the grant monies not only to do their work, but also to pay for universities’ costs. Wood argued that the bargain works mostly in favor of the universities, because they ride along on the substantial streams of research revenues their scientists bring in. While scientists were not exactly disadvantaged thereby, Wood suggested that they could prosper as much outside the university as in, raising the question that logically follows: who needs whom?

Since 2011, academic scientists have largely stayed put in the universities. “Who cares what universities charge for their services, as long as we are left alone to ‘do science,’” was the prevailing sentiment. Such a blasé attitude is no longer viable. While scientists busied themselves at their benches, the terms of the bargain have been steadily shifting to scientists’ disadvantage. The unique attractions of academic life are relentlessly, if slowly, falling away. Tenure is on its way out. Freedom of inquiry is increasingly constrained. Pushy administrators presume to dictate hiring, promotion, and curricular decisions that should sit squarely in scientists’ hands. Faculty governance has become mostly performative, with no power to make decisions stick—particularly budgetary and personnel decisions, which have become concentrated in the hands of administrators, governments, and favored political activists. Accreditation boards brazenly impose political agendas on faculties of science and engineering. Challenging the new racial / gender / sexual orthodoxies can snuff out careers in the blink of an eye.

In short, academic scientists can no longer assume that they will just be left alone to “do science.” In this new academic ecosystem, the scientist is looking more and more like a galley slave, whose life has come to be governed by a variation on the motto of Quintus Arrius1, the galley captain in Ben Hur: “Maximize grant revenues, churn out papers, and live!” Never mind that science, like God, moves on its own insistent, sometimes inscrutable timetable, which will not be moved along any quicker by lashing scientists to the oar, no matter how strong the administrative will to do so. For academic scientists, the question no longer is “who needs whom?”, but rather “who serves whom?” This means it is no longer possible for scientists to be indifferent to whether the universities are their natural home.

It’s worth noting that science and universities have not always been so tightly bound to one another. Their long-standing affair became a marriage with the post-WW2 expansion of federal spending on academic research. This spending has supported scientists, to be sure, but it also has enriched, empowered, and emboldened university administrations to wield power over their science faculties in ways they would not have contemplated a generation ago. In short, it is money that has broken the bargain, and it is scientists (or, rather, the substantial revenue streams they bring in) who have been dragooned into footing the bill. By staying put in the universities, scientists have largely ceded to others their traditional control over their profession, and the universities are increasingly disinclined to give control back. Indifference—wanting to be left alone to “do science”—is now complicity. It is time for scientists to act on Wood’s question and leave the universities.

But how? Perhaps scientists should take a leaf from their colleagues in law and medicine: organize into autonomous professional firms. Let us call these Independent Science Faculties, or ISFs. Here’s how such a thing might work. Imagine that a group of academic biologists working at (for the sake of argument) Simplicio University (SU) decide to leave and organize themselves into an ISF firm (for the sake of argument), Salviati Life Sciences, LLC (SLS). SU now faces a choice. It could hire, at great expense and disruption to its mission, an entire new life sciences faculty. Or it could enter into a contract with SLS to provide the educational and research services its formerly on-board biologists had provided. SU could continue to offer its students a biology curriculum, and SLS could deliver the top-notch education its members had always provided.

On the surface, such an arrangement seems to complicate what is already done in the traditional academic model. The major difference is that SLS biologists could now deal with SU from a position of independence and autonomy that they would not enjoy had they remained SU faculty. Suppose, for example, that SU administrators had taken it into their collective heads to impose an ideology that its science faculty found inimical. As SU faculty (employees, to be frank), they would have had little choice but to knuckle under. As SLS faculty, however, they are under no obligation to accommodate the SU administration’s folly, and SU would be in no position to impose its foolish whims. The biologists of SLS would be freer and more in control of their profession.

Numerous obvious questions arise from this seemingly simple proposal. What of tenure? What of intellectual freedom? How would scientists be paid? How would research work? Would it be the death of the university? Would it be the death of science? These questions, important as they are, all boil down to one: would science be better off under the status quo, or out from under it? That is a very large debate to be had, but it’s looking more and more like the status quo is no longer to the benefit of science.

Turning to education, the balance sheet is tilting more toward leaving the university than staying put. Universities have become sclerotic, deeply politicized, and administratively bloated behemoths. Protectionism and parochialism are commonplace. They will not change unless forced, and few seem willing to try. In this regime, students are no longer seekers of knowledge, but particles in a revenue stream that must be confined to the university. This is how “retention,” not excellence, became the teaching faculty’s mandate, whether they liked it or not. At our hypothetical Simplicio University, this means keeping the science faculty tightly “siloed,” constrained to teaching tuition-paying SU students only, and keeping those revenues coming, no matter how tepid their students’ performance.

This model may have worked when universities held a near monopoly on knowledge and could be selective in who they admitted. It doesn’t work so well in our increasingly networked world, where the acquisition and delivery of knowledge can no longer be confined to a secure revenue pipeline. Students are now able to navigate through a smorgasbord of information and instruction. As media production becomes cheaper and easier, scientists have expanding pedagogical options at their disposal. Universities are not at all prepared for the leaky pipeline, however, Exhibit A being their bungled response to the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, as academic administrations all across the country were forced suddenly into the networked online world. In short, when confronted with the networked world, the universities’ business model failed utterly.

Would ISFs have managed it better? Arguably, yes. Imagine our hypothetical Salviati Life Sciences represented one node in a network of numerous ISFs organized around the life sciences. SLS need not be under any obligation to restrict its services to SU students only. It can “unsilo” itself to offer education to any student from any university with which SLS has a contract. It could even act as a freelance provider. In short, SLS can meet the needs of students navigating through the complex web of knowledge in ways that the turgid universities cannot manage. As part of a larger network of life sciences ISFs, SLS is also now brought into a competitive marketplace, which brings market discipline, and, markets being what they are, incentivizes innovation and adaptability in ways that universities cannot.

What of tenure? Wouldn’t moving scientists out of the university and into ISFs jeopardize their freedom to explore science’s “endless frontier”? Wouldn’t leaving the universities turn scientists into a mob of competing “contingent faculty” compromising scientific progress and leaving them ever more under the thumb of university administrations?

Actually, that’s perilously close to the situation facing academics today. Contingent (also called adjunct) faculty are responsible for more and more collegiate instruction. Indeed, tenured professors are a shrinking proportion of the university’s teaching personnel. University administrations are returning to the ‘hired man’ concept of faculty—that faculty are employees of university administrations and serve at their whim. This is why more and more scientists are finding out the hard way that their university administrations are brazenly willing to stick a shiv between their ribs, niceties of tenure notwithstanding.

There is more than one way to skin the intellectual freedom cat, and done correctly, ISFs represent one. Science has always drawn strength from scientists organizing into self-governing, autonomous guilds of like-minded professionals. The academic science department represents one such type of guild, wherein training, advancement, and tradition rest mostly in the hands of the department faculty. That autonomy is being relentlessly stripped away, however, and intellectual freedom is going with it. The challenge for scientists is to restore their guilds and the protection they provide.

An ISF modeled after, say, a law firm might be one way. A university professor would very likely feel at home in a law-firm-model ISF. Law firms organize themselves into hierarchies of rank, like academic departments do. At the top are senior partners (professors), followed by partners (associate professors), then junior partners (assistant professors), along with a host of interns and paralegals (graduate students, post-docs, volunteer undergraduates). In both law firms and academic science departments, people advance through ranks through rigorous procedures of development and evaluation, including performance, contributions to the firm, and the opinions of respected peers. In short, recruitment, promotion, and advancement decisions sit squarely in the hands of the firm partners. In universities, such decisions are coming to rest more and more in the hands of ideological commissars who serve at their administrations’ pleasure and have the power to impose their will on faculties.

But, again, what of tenure? Law firms actually have a kind of tenure system, the principal difference being how peoples’ positions are secured. Presently, academic scientists’ job security depends upon the flimsy promise of tenure. In a law firm, partners’ security rests upon having an equity stake in the firm. This arguably offers better protection to partners than tenure does to professors, because universities’ abuse of tenure will carry real costs when equity shares are at stake. Suppose, for example, that Simplicio University would like to rid itself of the inconvenient Professor Becket, a troublesome biologist. SU has the power to remove Professor Becket, tenure protections aside. It can use its deep pockets to out-lawyer Professor Becket, for example, as the University of Pennsylvania is doing with Amy Wax. It can orchestrate an academic mobbing against Professor Becket, or it can drag him into HR Star Chamber tribunals on trumped up policy violations from previous decades. In the end, SU would win, because its pockets are much deeper than Professor Becket’s.

Things would be different if Professor Becket was a senior partner of Salviati Life Sciences. Removing him would impose real costs on SLS, because it would entail the other partners buying out his equity stake. This sobering reality can help guard against the sordid practices universities now use to strip inconvenient academic scientists of their tenure. Professor Becket would have more intellectual freedom as well, because it would be secured by his equity, not by an easily revoked promise of tenure.

Finally, what of science itself? Academic scientists enjoy support from their universities in the form of laboratories, libraries, management of grants, and so forth. How would that work in an ISF? This is perhaps the easiest concern to address because there are already many successful examples of independent research institutes from which to draw, in fields ranging from cancer research to ecology. Scientists in such institutes can apply to the same research funders that university scientists presently do. An ISF would be, in many ways, an expansion of the research institute model.

The major difference would be to introduce a level of competition on the prices universities charge for their support. These are assessed as a surcharge to research grants, known as indirect costs or overhead, charged as a percentage of the direct costs of doing the science. Presently, indirect costs rates on research grants average about 53% of direct costs.2 These rates are two to four times higher compared to other countries with national research programs. Many research funders, like the Human Frontier Science Programme cap indirect costs at 10% of direct costs, with no harm done to the science they support. There should be ample room to bring down indirect costs without affecting the quality of research.3 Why not such a cap across the board?

Indirect costs are the third rail of science funding, however. Like Social Security, any attempt to reform indirect costs funding is met by a vociferous mob, not of gray-haired pensioners, but of politically well-connected university administrators. Indirect costs have thus become a form of politically untouchable corporate welfare to universities. Networks of competing ISFs could incentivize rational indirect costs reform in ways that are impossible when science is dominated by universities.

In the end, it will all boil down to a simple question: which model will be more attractive to scientists? If done right, scientists in ISFs could have more secure employment, enjoy greater intellectual autonomy, and be freer to innovate and take risks than their present university positions will allow. It’s time for scientists to make the jump.

J. Scott Turner is director of the Intrusion of Diversity in the Sciences Project at the National Association of Scholars, from where this article is republished.

1 “You live to serve my command. Row well and live!”

2 The range is from about 45% to near 90%.

3 Noll, R. G. and W. P. Rogerson (2010). The economics of university indirect cost reimbursement in Federal research grants. Challenges to Research Universities. R. Noll and L. R. Cohen. Washington, D C, Brookings Institution Press.